Atheneum and the Hermit of Abram’s Point

by Frances Karttunen

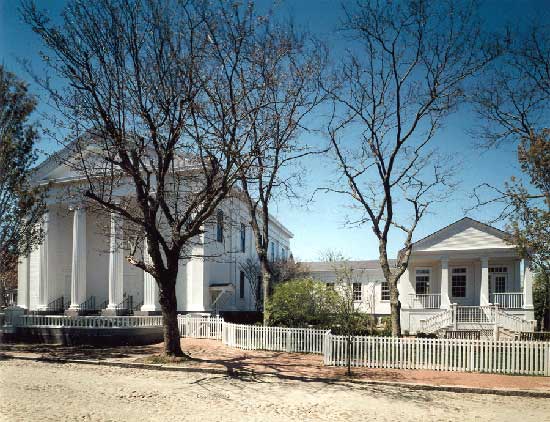

The Nantucket Atheneum, one of Nantucket’s most imposing buildings, stands at the corner of Federal Street and India Street facing the considerably less imposing neo-Georgian downtown post office.

Both are replacement buildings. The Atheneum, designed by architect Frederick Brown Coleman, was built in a mere six months on the ashes of the previous Atheneum. That building, originally a church that had been adapted to secular use, was destroyed in Nantucket’s Great Fire of 1846.

The earlier Atheneum building, though smaller, was also graced with tall white pillars across the front. In its public lecture room Frederick Douglass delivered his first address to a mixed-race audience, and there Nantucketers assembled to hear from many celebrities of the first half of the 1800s. After the loss by fire of the Atheneum’s books and its irreplaceable collection of artifacts from the islands of the Pacific, a concerted public effort filled the new building with more books and brought an unending stream of speakers and entertainment upstairs to its Great Hall. Douglass returned repeatedly to speak to admiring audiences. Now restored and as lovely as ever, the Great Hall continues to serve diverse needs of the Nantucket community: library reference, internet connections, public speakers, literary events, concerts, and entertainment galore.

The brick post office across the street, also serving Nantucketers’ crucial needs, was a Depression-era project to put Nantucket men to work and to move mail handling from the first floor of the Masonic hall on Main Street. Itself a relatively fireproof building, the post office did not rise on the ashes of some unstoppable conflagration. In 1934 a beautiful 19th-century house, worthy of architect Coleman himself, was demolished to make room for it. What had been a visually pleasing intersection became less so, but the proximity of post office and library has been a public convenience for nearly three quarters of a century now.

The Atheneum

Sadly, the Nantucket post office is not graced with WPA murals, but the Atheneum does have a distinguished art collection. Just inside the entrance, on either side of the main door, hang large oil paintings. One is of astronomer Maria Mitchell, the Atheneum’s first librarian. Soon after the opening of the new building in 1847, she discovered a comet from a nearby roof-top observatory. For this she won a medal and was launched on an academic career. The Atheneum’s loss was Vassar College’s gain. Her portrait by the door celebrates a local daughter gone on to greater things.

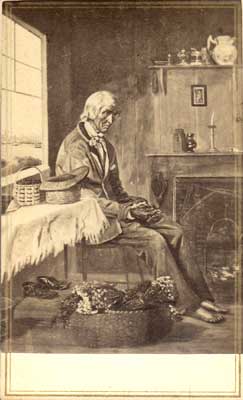

The other portrait is of an elderly man sitting at a table in his modest home. He is simply dressed and barefoot. Under the table lies a pair of shoes. There is a basket of berries on the table, a big basket of herbs on the floor, a candlestick on the mantle and a large pitcher on a shelf above the fireplace. The man’s back is to an open window through which the town of Nantucket can be seen across the harbor. This is a “last Indian” genre painting. It could be painfully sentimental, but it is not.

The man is Abram Quary. When he died on November 25, 1854, at the age of 82, only one other Nantucket Wampanoag remained, a woman known as Dorcas Honorable. Both Abram and Dorcas had survived their spouses and offspring by decades. Dorcas, however, was a gregarious sort, having had five husbands in the course of her long life. Abram lost his first wife after nearly a decade of marriage and waited four years to remarry. Somewhere along the way he also lost an only child, and with that his enthusiasm for human companionship apparently dried up. He lived alone in Shimmo and made a point of letting people know when he wanted company (sometimes) and when he did not (often).

Abram Quary was born in 1768, five years after the “Indian Sickness” had all but wiped out Nantucket’s Wampanoags. Few children were born after the epidemic; Abram and Dorcas were exceptions. Because they were temperamentally so different, they probably had little to do with each other in life, but like a bereft spouse, she survived him by only six weeks. Nantucket historian Obed Macy claimed that Abram was half-white. His surname was, however, Wampanoag. Quary is an abbreviation of a name that is documented in several forms: Skootequary, Skuotquaty, and Skutquade, among others. According to Benjamin Franklin Folger, another 19th-cenury Nantucket historian, Abrams’ grandfather was Joseph Quary, whose home was a wigwam on the west side of Sesachacha Pond, and Abram’s mother, Sarah Quary, was an expert basket maker.

As a young boy Abram (short for Abraham) was placed in the home of Nantucketer Stephen Chase for several years. Then, like most Nantucket boys, he went whaling. At age twenty-five he married the young widow Abigail Dingle, and years later, as a widower himself, he married a woman named Fanny Hall. In a conversation with the Rev. Phebe Hanaford, he spoke sorrowfully but resignedly of the death of his child.

By the 1840s Quary was living in a little house on the bluff in Shimmo that now carries his name: Abram’s Point. The land on which the house was located belonged to Hezekiah Swain, and Swain was said to do an annual spring plowing for Abram Quary’s garden.

To support himself in those later years, he sold dried herbs from the garden and berries he picked on the commons. A master basket maker like his mother before him, he could weave a basket of beach grass as a novelty, but he made sturdy baskets to sell to Nantucketers. A number of these baskets survive to the present, looking just like the ones in the painting.

What made this otherwise reserved and unsociable man a local celebrity in his own right was not his basket making, however. After leaving the sea, he had turned to clambakes. George Worth, who was born in 1809, recalled Abram Quary as “the prince of Nantucket caterers” without whom “no evening entertainment was deemed complete.”

As he became more withdrawn from human society, Quary would raise a white flag on a pole outside his house in Shimmo to signal the townspeople that he had been clamming and was ready for visitors. A Nantucket woman told Benjamin Franklin Folger that she had been to a pre-arranged September clambake at Quary’s place, and that his house “was situated near enough to the seashore to make it a very convenient spot for these parties, known to us by the name of squantums.” Apparently partygoers sailed up-harbor to Abram’s Point. The woman also remarked that Abram Quary had preternatural powers of observation: “He was never seen to look at any of us, yet he took note of everyone there, and he was particular to inquire into the pedigree of those whom he had never seen before.”

This photograph of a painting of Abram Quary, last Indian on Nantucket, hangs in the Nantucket Atheneum.

PHOTO COURTESY OF NANTUCKET HISTORICAL ASSOC.

In 1851 a woman he had certainly never seen before—a German-born, portrait painter named Herminia Borchard Dassel—arrived in Nantucket and rented space in the Atheneum to exhibit samples of her work. Dassel had come to the island to paint a portrait of Maria Mitchell, a very unwilling sitter, and then she did a pair of oil portraits of an even more unlikely subject, Abram Quary. Maria Mitchell remarked that Quary was flattered by Dassel’s interest in him. He permitted her to come to his house and paint him there, and he even helped her compose the painting, insisting on posing shoeless.

At the time Herminia Dassel was painting her portraits, people were flocking to studios for the newest novelty, daguerreotype portraits. Abram Quary sat for one of them too, which is how we can confirm that Dassel caught a good likeness.

Dassel put the finishing touches on her portrait of Abram Quary in her rented studio space, and it never left the building. A group of Nantucketers purchased it seventy dollars in order to donate it to the Atheneum.

Not long afterward, people who kept a watchful eye on the aging man convinced him, for his own safety, to move into town and take up residence at the Asylum. He didn’t live much longer, and two years after his passing, his little house burned to the ground. What remains is the moving portrait that hangs to this day in the Atheneum.

Frances Karttunen’s books, The Other Islanders: People Who Pulled Nantucket’s Oars and Law and Disorder in Old Nantucket are available at Nantucket bookstores.