Polpis Road: U Mass Field Station

Resident Scholars

by Frances Kartunen

Lying between the uplands of Shawkemo and Quaise, Folger’s Marsh is one of the loveliest spots on Nantucket. On the north side of Polpis Road, fronting on the saltmarsh, is the Life-Saving Museum, a replica of Nantucket’s Surfside Station. A visit to the museum yields not only a glimpse into heroic sea rescues of the past but a sweeping panoramic view of the Nantucket’s most pristine tidal estuary, where—at the right time of year and on the right tide—one can watch white egrets and great blue herons regally stalking about the landscape. Bringing along binoculars greatly enhances the experience.

Across the marsh on the Quaise side is the University of Massachusetts Field Station, a facility dedicated to studying the ecology of Folger’s Marsh and much more. The well-marked driveway to the field station is on the left side of Polpis Road uphill after it crosses the saltmarsh. At the terminus of the long driveway is a parking area where visitors are asked to register on a sign-up sheet. Starting at the parking area, the field station’s hundred acres are crisscrossed by walking trails offering views of the saltmarsh, a freshwater pond, Nantucket Harbor, and—beyond the sandy spit of Coatue—Nantucket Sound.

The field station got its start as the private estate of Stephen Peabody, who requested in his will that his property be used for scientific teaching. After some searching and negotiating, his land was at last transmitted to the University of Massachusetts in 1963. Initially it was administered by the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and used by its faculty and students for conferences, courses, and research projects, but soon the then-new Boston campus became involved. In 1969 the first summer field biology course was conducted by staff from UMass Boston’s biology department. In addition to scientific teaching and research, the field station became home to summer humanities and theater arts courses.

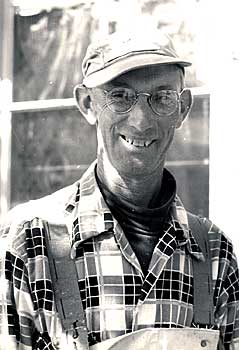

As soon as Stephen Peabody’s estate was transferred to the University of Massachusetts, J. Clinton Andrews was hired as Resident Naturalist and Technical Assistant. He and his family moved to the field station in September 1963 and lived there year-round until Clint’s retirement twenty-one years later.

Edith & Clint

Descended from Nantucket’s first English settlers and themselves third-generation fishermen, Clint and his brother George knew Nantucket waters as few others ever have in recent years. To support themselves through the Great Depression, they fished by hand line, long line, rod and reel, eel spear, and clam rake. They knew how to haul scallop dredges and lobster pots under sail and under power and how to land dories full of codfish through the surf.Clint not only practiced all these skills, he thought and wrote about them. His book Fishing Around Nantucket, illustrated by the author himself and published by the Maria Mitchell Association, is a classic.

Cornell-educated Edith Andrews says she never had a University of Massachusetts job title during the years they lived at the field station, but she is an eminent ornithologist—the only woman yet to be inducted as an honorary member into Harvard’s Nuttall Ornithological Club. While residing in Quaise, she netted and banded birds and rehabilitated injured ones that were brought to her for care. She also built an unparalleled research collection of prepared bird skins, each precisely annotated with the date and circumstances under which it had been found dead or dying. The skins are now housed in state-of-the-art cases in the Maria Mitchell Association’s natural science department, and in December 2006 the Association honored Edith by naming all their bird holdings, old and new, the Edith Andrews Ornithological Collection.

Ginger Andrews was about ten years old when she and her parents moved to Quaise. There, by her own account, she enjoyed an enchanted childhood among a host of feathered companions. Among them were Gulliver the gull and Owlbert the one-winged barn owl. Owlbert apparently managed to attract a lady-love despite his impairment and fathered a brood of six owlets that lived in a field station garage and were fed every night by their mother, who came and went on silent wings, leaving off mice for the babies.

There was also Noah’s Auk, an injured razorbill (the closest thing to a penguin to be found in the northern hemisphere), who spent a great deal of time in the family bathtub, and Henry, a disabled night heron who lived in a converted rabbit hutch on the edge of the field station’s freshwater pond. Henry survived for 13 years feasting on the remnants of golden shiners, a fish with which Stephen Peabody had stocked the pond. Unfortunately for Noah, when he was released, he joined Henry at the pond and was so gluttonous in his consumption of golden shiners that he literally ate himself to death.

Edith recalled that they also provided a home for a red tailed hawk and a banded short-eared owl that was found dead at Tom Never’s Head just three weeks after release at the field station. “There were so many tragedies,” remarked Ginger, “that I put them out of my mind.”

Not all the transients were feathered. Ginger continued, “Dad had a raft in the saltmarsh where he would raise oysters, and we were having lunch one day when a little harbor seal hauled itself out on the raft right in front of the house. It took a nap and disappeared again. And I was late to school one day because I had seen a great big ocean sunfish stranding in the harbor right down in front. Dad had to go push it off. It was terribly exciting, and I got a ride to school that day instead of having to ride the bus.”

As for the academic work that went on at the field station, for some students it involved a semester in which they learned about the physical history and geology of the island, the Wampanoags and the English settlers, the plants, animals, fish, and birds. Some of the students were sent in to town to locate George Andrews’s boathouse on North Wharf, which was described to them as “a building completely integrated into its environment.”

Ginger’s impression of the early days of the technical writing course, in which her father enrolled along with the students was that it was “Kind of surreal. On a nice day they would be dotted along the edge of the bluff with typewriters on little metal typing tables with folding metal chairs in this beautiful landscape, the whole of the harbor in sunshine, typing away on their technical descriptions.”

In 1974, Dr. Wesley Tiffney Jr. left the University of Massachusetts Department of Biology to join the Andrews family as year-round Resident Director of the field station. Ten years later the retirement party for Clint Andrews marked beginnings as well as endings. The party initiated a tradition of annual Christmas pot-luck dinners hosted by Wes Tiffney and Susan Beegel for the field station’s many Nantucket friends, while for Clint and Edith retirement brought a move to Madaket Road and continuation of their active life as Nantucket naturalists. Fishing Around Nantucket, with a foreword by Wes Tiffney, was published in 1990. Meanwhile, Edith has maintained her ornithological record-keeping to the present while teaching generations of Nantucketers and visitors to see and appreciate the island’s birdlife.

Whatever the accomplishments of the many UMass students and researchers who have lived and worked at the field station over the years, the lifetime achievements of its resident members of the Andrews family in and of themselves are ample fulfillment of Stephen Peabody’s vision.

Many thanks to Edith and Ginger Andrews for help with this column.

Frances Karttunen’s book, The Other Islanders: People Who Pulled Nantucket’s Oars, is available at bookstores and from Spinner Publications, New Bedford. Look for Law and Disorder in Old Nantucket in bookstores this summer.